At Gallup, Frank Newport offers some data that are broadly consistent with

Henry Olsen's analysis of GOP factions:

The Republican Party in general has a disproportionate percentage of conservative and highly religious Americans in its ranks, so Cruz's strategy would appear to make numerical sense -- as it would for other conservative politicians, like Mike Huckabee or Scott Walker, who may aim for the same target audience. On the other hand, potential candidates like Jeb Bush or Chris Christie would play more to Republican voters who are in the moderate and perhaps less religious space of their party. All of which raises the question: Exactly how big are these various segments of the Republican Party?

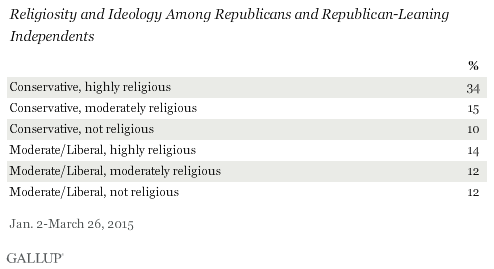

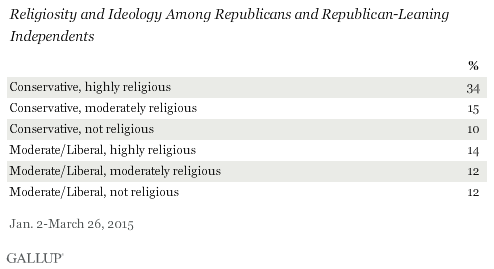

We can provide estimates by looking at the cross between ideology and religiosity among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, based on interviews conducted with 17,845 Republicans as part of Gallup Daily tracking so far this year.

These data make it clear how much Republicans in general skew both religious and conservative. Overall, 50% of Republicans are highly religious, above the national average of 40%, and 61% are conservative -- again, way above the national average of 35%. But not all highly religious Republicans are conservative and vice versa. In fact, the data show that a little more than one-third of Republicans can be classified as both conservative and highly religious. Thus, the pure segment of Republicans who meet both conservative and highly religious criteria is not the majority. Cruz would argue that his goal is to maximize the turnout of this group. And it's reasonable that in some primary and caucus states, the base of conservative and highly religious Republicans could outperform their representation in the overall GOP population. Still, highly religious conservatives constitute a minority of the Republican Party.

Also note that not all highly religious conservatives are part of the Christian Right. One can be highly religious and still put economic issues ahead of social ones.

Jeb Bush

Jeb Bush